I grew convinced that following water, flowing with it, would be a way of getting under the skin of things. Of learning something new. I might learn about myself too.' - Roger Deakin

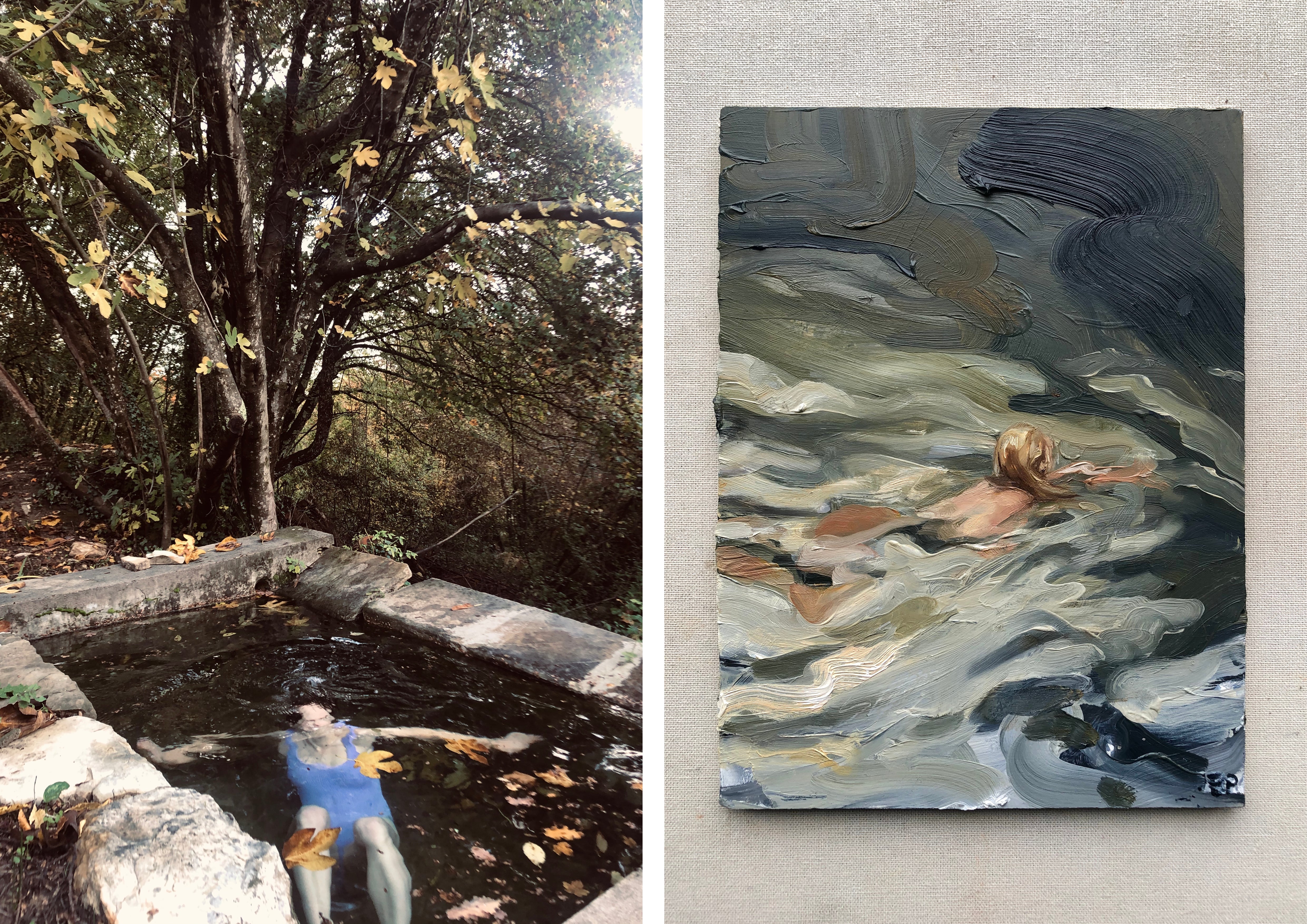

It's early morning in the hills of Tuscany and artist Emily Ponsonby is venturing through a brambly wood to a plunge pool she discovered just days before. Skinny-dipping mornings have quickly become the routine here, followed by her painting sessions in the rural farmhouse she is currently renting. This beautiful pool almost feels like it's been sent here, says Emily from the large kitchen where she paints - mainly female forms, swimming in the oily depths of water - onto her canvas. There's nothing greater than complete submersion, it's so cleansing and so remedial, she adds.

As if by osmosis, the greenish hues of the plunge pool are revealed through thickly painted layers of oil and beeswax. I feel very free here and when I'm painting it just flows out of me - everything has become green in my work because there's so much green around, says Emily, laughing. The characteristic Tuscan light reflecting on the water also brings a golden tone to her newer works along with a sense of liberation in the brushstrokes, which she explains, is imparted from her own feeling when in the water. I'm quite sensitive and that's why I paint and how I paint. Whenever I feel this big dark cloud upon my shoulders, I have found that the minute I plunge myself into a pool or the sea or a river, it's just like a new chapter and the cloak is lifted.

Having studied at City & Guilds Art School in London for her art foundation followed by Leith School of Art in Edinburgh before attending the Royal Drawing School, Emily's extensive training not only equipped her with painterly techniques but allowed her to look at art in an entirely new light. Growing up I was used to seeing gentle, classical paintings and suddenly [at art school] I was challenged to question what can the material do and how can the subject reach through you, into the materials and onto the canvas. I learned I could place emphasis on a single stroke and look at what that means. It really made me fall in love with painting.

After graduating, Emily lived and worked in London before moving to Cape Town, South Africa, where she combined painting with pottery and yoga. I loved how all three really fed into each other; I was moulding bodies out of clay, which was so physical, and then I was also painting so it all started to flow. The twisting and awakening every bit of your body is actually very similar to cold water swimming, says Emily. Working in Cape Town last year, Emily began experimenting with material, too, painting onto layers of vivid red soil along with chiffon and canvas, before peeling away the top layers to reveal the paint imprinted underneath. It was while I was painting in South Africa that I was drawn to the idea of painting a state of mind, rather than a representational portrait of a specific nude.

Emily's fascination with being in the water has informed her latest body of work and each of her paintings explores the uninhibited relationship between the naked body and the water; each painted figure displays a weightless, dissolving and undiluted vitality and the sense of freedom is palpable. I've been very classically trained but my time at the Royal Drawing School taught me to paint almost in the manner of what you're painting, she explains. If you're painting the bark of a tree, say, then it shouldn't be drawn or painted in a smooth way because there's nothing smooth about a beautifully rugged old oak tree! You've got to be completely in the zone. I almost close my eyes, it's like a dance spilling onto the canvas.

The small scale paintings Emily is working on from Tuscany is a new development since the first lockdown in the UK when she began reading poetry. While small, the 20 x 15 panels convey much bigger emotions and sensations than their diminutive size. I really wanted to get across this feeling of plunging into the water in something so small, like putting a novel into a tiny one-page poem. Emily's process does not involve extensive preliminary sketch work, she simply sketches once at the location, whether it's a river or pool, and concentrates on the feeling of the water flowing over her. It's this sensation that she translates onto the canvas, for us the viewer to be transported by. Water isn't just one big, soft stroke throughout the whole painting, she says. It is so choppy and I use many different brush strokes to try to make it feel as real as it possibly can, allowing the materials to do the speaking.

Emily's current materials include beeswax and oil paint. Based on the ancient Egyptian Fayum Portraits, the encaustic painting process involves melting down beeswax, which makes the room smell like honey before brushing it over her canvas. Once it cools, Emily begins to paint with a lightness, speed and sense of freedom in her brushstrokes. It's sort of a constant battle of being really free-flowing but then pulling out a figure, which I almost always overwork, she explains. But that's the best moment because I free it all up again with really thick brushstrokes, digging back through the layers, in a really physical way, to reveal a figure, she adds. So often in my work I use the tip of the paintbrush far more than I use the correct brush end!

Not unlike the words of the writer and environmentalist Roger Deakin, Emily is following the water, flowing with it and learning something new with each piece she creates. Roger Deakin was just such a marvel and I often read something from him in the morning to get me in the right state of mind before I begin to paint, says Emily. There's a moment when I'm working on a painting, when it suddenly becomes alive and I feel light. There's no more searching or pulling and I'm free of angst. That's when I know it's time to put my paintbrush down.

For more information on Emily's current body of work, see her website.

Words by Andie Cusick.

Images by Emily Ponsonby.

Add a comment