Fossil hunting, somewhat fittingly, was a late comer to the natural sciences, with its beginnings in the 17th century.

Victorian fossil collector Mary Anning worked along the unstable Blue Lias cliffs. Fossil hunting was a slippery business, particularly for a working class woman at the time. The same landslide that unearthed Anning's first complete Ichthyosaur also buried her beloved dog Tray. Anning who had already been struck by lightening once as a child, worked during stormy winter months when layers of limestone and shale broke away to expose our prehistory. It was in December 1828 when she found a pterosaur, the flying, furry coated dragon with its hay day in the late Cretaceous Period. Its remains were unearthed alongside ammonite shells, belemnite fossils (sold as devils fingers') and other treasure which Anning collected for display in her fossil shop, Annings Fossil Depot.

Annings Fossil Depot

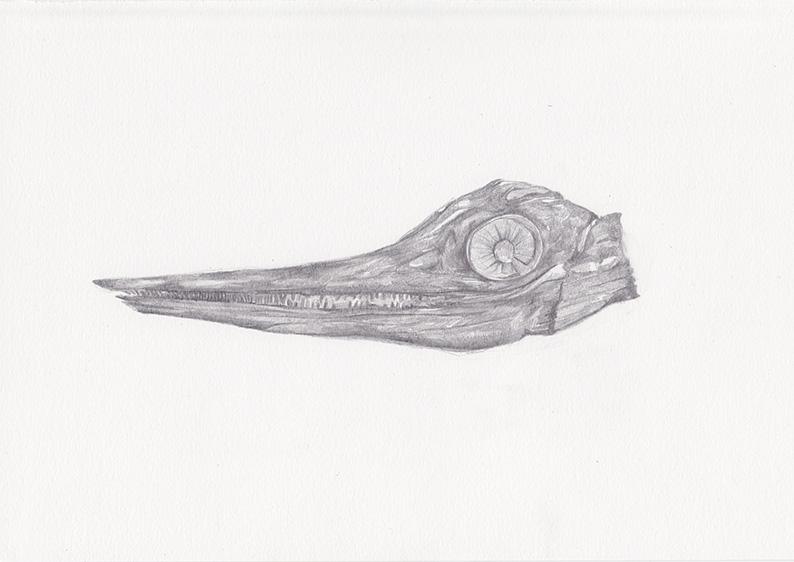

Ichthyosaur

Ichthyosaurs look like dolphins and were mislabeled at the time of their discovery, their teeth were often mistaken for crocodile teeth, while their elongated, boney smiles were said to be the creation of the devil. Used by the clergy to support deluge flood myths, this fossil sometimes subverted science, while forever changing perceptions about life on earth, Ichthyosaurs pointed a dorsal fin at ancient creatures like the plesiosaurs and the mosasaur.

Ammonite

Ammonites, known as snake stones, were free swimming molluscs that lived and died with the dinosaurs. Like a squid sticking out of a snail shell, the animal lived in the last and largest of a chain of spiralled chambers. These super snails were successful predators and their fossils are the most prolific fossils along the Jurassic coast, materialising in a range of sizes, from only a couple of millimetres across to over two metres in diameter. Ammonites can be credited for teaching us about the disposition of land and sea. But still, the question remains: why hasn't even a single ammonite survived?

Brittle stars

Brittle stars are the 90 million year old relatives of the starfish. Known also as serpent stars, they use five flexible arms to wriggle across the seabed often at depths greater than 200 metres. Many fossils found on Eype clay have their legs trailing in the same direction, suggesting a storm or tsunami may have smothered their community around 180 million years ago. Like all geological finds, this is only a partial picture of the past, and could be contested with fossil evidence that does not fit this picture. Piecing together the puzzle of mother earth is the very crux of fossil hunting.

Words by Kate O'Brien, Editor of Plant Magazine. Illustrations by Emily Jane Settle - instagram @emjsettle

Add a comment