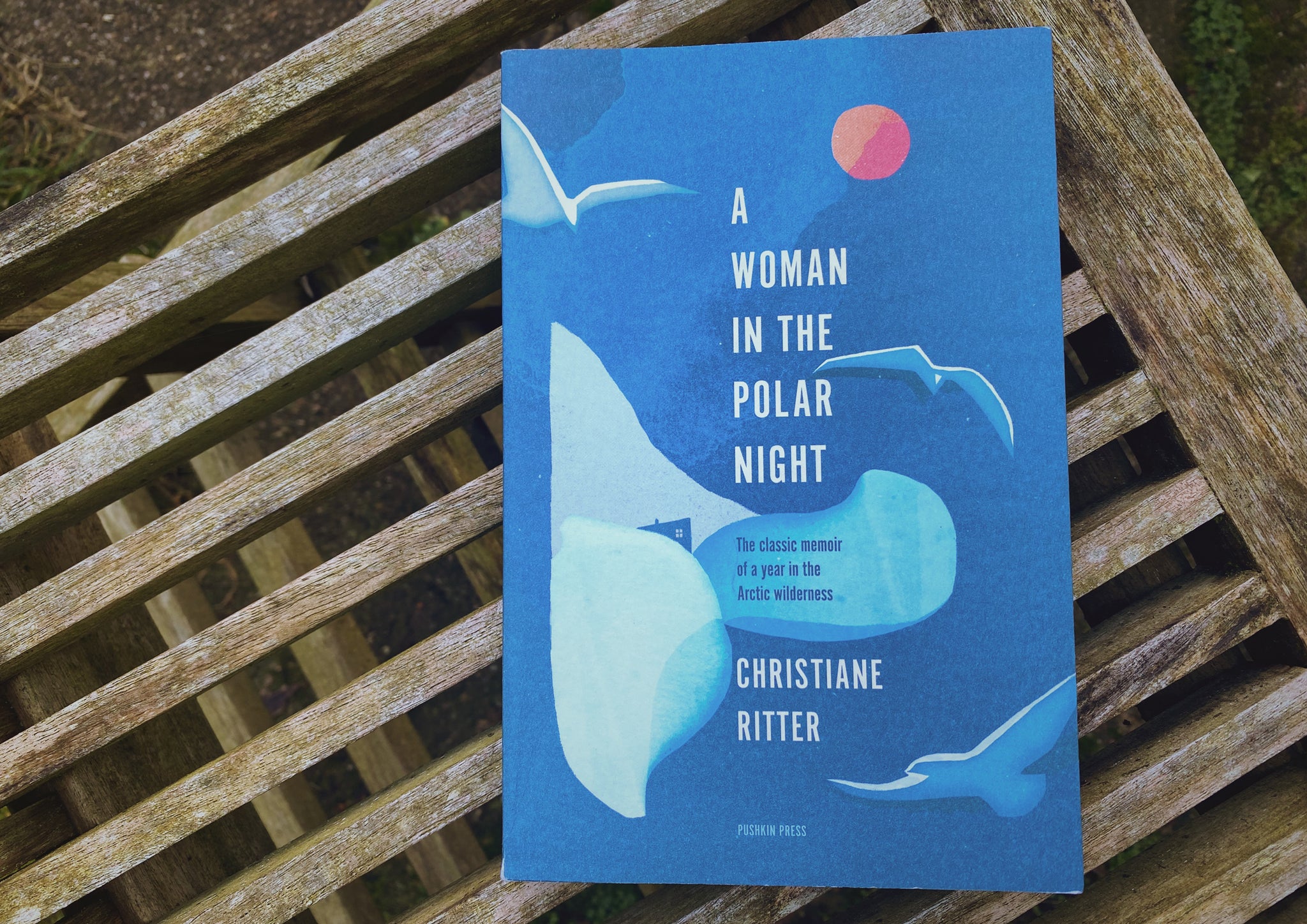

Every season I like to go through my shelves and make a list of weather-appropriate books I might pick up. Memoirs of a Polar Bear by Yoko Tawada is a title I’d like to get to before spring arrives; and I’ll always associate The Snow Collectors by Tina May Hall with this time of year. It’s cheerfully harmonising to match the page to the outside. I admit that today the sun is shining, it’s above freezing, and I’m not likely to run into a polar bear where I’m going, but still, I’ve decided to take A Woman in the Polar Night by Christiane Ritter with me on my walk today. The subheading is ‘the classic memoir of a year in the Arctic wilderness’, it’s translated from the German by Jane Degras, and it’s been calling my name for a while.

I read the opening chapters on the train. The book opens with: ‘to live in a hut in the Arctic had always been my husband’s wish-dream.’ This memoir is Ritter’s only published book, and it chronicles her time travelling to Svalbard in the 1930s to stay with her husband, who had remained there following a scientific expedition. I’m reminded of Lyra and Mrs Coulter packing for their travels in Pullman’s Northern Lights, as Christiane happily shops for ‘a feather bed, hot-water bottles, books, paint boxes and films, baking powder and spices, wool for knitting and wool for darning’, excited for her journey, before receiving a short letter from her husband instructing her not to pack anything she can’t comfortably carry in a rucksack, and (if she has room) enough toothpaste for two people for a year. He adds, jovially: don’t worry, ‘it won’t be too lonely,’ as their nearest neighbour is only sixty miles across the ice. Closing the letter with trepidation, Christiane prepares to set sail.

I disembark at Battersea Power Station, part of a new branch of the Northern Line, which drops me right beside its namesake. The power station was built at exactly the same time as Christiane’s arctic adventure, but has been out of action for forty years. It’s an imposing structure, one of the world’s largest brick buildings, and it was recently reopened as a mixture of flats and shops. Walking past it, down to the Thames, I turn west towards Battersea Park, where the Peace Pagoda sits by the river, its gilded bronze shining. Gifted to London by Buddhist monk Nichidatsu Fujii in the 1980s, Fujii was instrumental in the construction of peace pagodas around the world — the first built in Hiroshima and Nagasaki — as a pledge and plea for peace. I think of Ritter leaving Austria in the 1930s, travelling into the wilderness with no news of home, as grumblings of war began to creep across the land.

Entering Battersea Park itself, there are many elements left over from the Festival of Britain in the 1950s, including a fountain with an impressive water display that goes off once an hour in the summer months, a 1950s-style tea hut, and ornate walkways. Today the park is quiet except for the occasional dog walker, and I loop around the boating lake, pass the bandstand, and duck back out of the park near Albert Bridge. The cold wind hits me as I walk across the Thames, and with a shiver I pull my scarf out of my bag.

However, I’m nowhere near as cold as Christiane Ritter. Sitting on a bench on the north bank, I go back to her book. Having reached Svalbard, Ritter writes that ‘there are no days and no nights.’ In their makeshift hut, looking around for the bed that her husband had promised her, he merrily admits it hasn’t been built yet, as they’re currently waiting for the sea to throw up some wood. And so, stoic, she befriends an Arctic fox, tries to cook bread without yeast or baking powder, and navigates ‘new dimensions of time and space.’

‘The moon lights up Cake Mountain (the name we have given to one of the three Grey Hook peaks whose shape resembles a gugelhupf, the round and fluted Austrian cakes). But the spur of the mountain stretching in front of it is in shadow… These scenes are not made for human eyes… These scenes are changed by sorcery.’

After a few months, her husband and his friend are ‘seized by wanderlust’ and leave Christiane on her own for many days at a time. She must dig herself out of the snow every day, be mindful of bears, and — though it is terrifying — she has surprised herself by how she has fallen in love with the landscape; the way it both takes hold of and freezes everything. ‘The potatoes are also frozen,’ she writes in frustration and awe. ‘They are covered with a layer of ice and shine like Christmas tree decorations.’

Putting the book back in my bag, and pulling on my gloves, I decide to end my walk by heading to Brompton Cemetery, one of London’s Magnificent Seven. The chapel’s architecture is loosely based on St Peter’s Basilica in Rome, and it’s a maze of weather-worn headstones and catacombs. It’s also the resting place of suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst, and a squirrel is tugging at a purple sash that someone has left on her grave.

Pleasantly tired from my walk in the cold, I lose myself in A Woman in the Polar Night once more, on the tube home, marvelling at the way that Ritter copes with the unforgiving climate; how she confronts the never-ending night and manages to write about it all so beautifully, hypnotically, her words refracting colour in the dark.

‘Northern Lights of incredible intensity stream over the sky; their bright rays, shooting downward, look like gleaming rods of glass. …They seem to be falling directly toward me, growing brighter and clearer, in radiant lilacs, greens and pinks, swinging and whirling around their own axis in a wild dance that sweeps over the entire sky, and then, in drifting undulating veils, they fade and vanish.’

See a map of Jen’s walk, which is approximately 5 miles and takes about one hour and 50 minutes.

A Woman in the Polar Night by Christiane Ritter is published by Pushkin Press.

Jen Campbell is a bestselling author and disability advocate. She has written twelve books for children and adults, the latest of which is Please Do Not Touch This Exhibit. She also writes for TOAST Book Club.

Add a comment